If your cheap parmesan tastes terrible it’s because it’s not the real thing. I went to Parma to see how genuine, PDO protected, proper Parmigiano Reggiano is made and why it has a premium price tag.

‘So this cheese is twelve years old,’ says Simone Ficarelli, the international marketing officer of Parmigiano Reggiano, expertly wielding the short, stubby, knife that’s the traditional tool used to break off chunks from the giant wedges.

There are white lumps in it, a distinct mark of a mature cheese. These are calcium lactate crystals, and are perfectly safe to eat. In fact the crystals in Parmigiano Reggiano cheese are a sign that the cheese has been properly aged. When you eat the cheese the crystals spark out a nutty flavour that complements the saltiness.

DOP Parmigiano Reggiano has been made for over 900 years and is only produced in the provinces of Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna to the left of the Reno river, and Mantua to the right of the Po river. This is the area of the farms where the cattle for the milk are fed on locally grown forage. It can only be made with this skimmed cow’s milk, salt, and rennet for curdling.

The cows live in airy open-sided barns, with extra fan cooling in summer, and they eat bundles of the lush grass that surrounds them. Strict rules ban the use of silage, fermented feeds and animal flour. They seem very happy, with plenty of room to move, and their waste is regularly pushed out and used for the farmlands. Water is carefully rationed for cleaning, no more than is necessary. This is an eco conscious process with rainwater collected from the giant roofs

Making milk into magic

TIn the dairy later, suitably attired in hair net and white coat, I learn more. Their milk then travels just a hundred metres to the next door dairy where, after being left long enough for the cream to rise and be skimmed off, it’s poured into traditional copper vats to be heated. It takes about 550 litres of milk to produce one wheel of Parmigiano Reggiano.

Rennet is added to curdle the milk and I watch the expert cheese makers sift the milk through their fingers to check the process. It’s a skill that a machine cannot emulate, only experience can work the magic.

When the expert decides the time is right, a large ‘whisk’, a traditional tool called a “spino”, is used to break up the curd into smaller pieces. It’s hard work but the men cheerfully put their backs into it. This isn’t just a job, this is a labour of love.

The cauldron is heated to 55 centigrade, and the granules slowly sink to the bottom forming a single mass. After about fifty minutes the large lump that’s formed is divided into two with a large wooden paddle and these are lifted out in muslin bags. The remaining liquid, the aromatic whey, will be sent off to feed local pigs and give us delicious Parma ham.

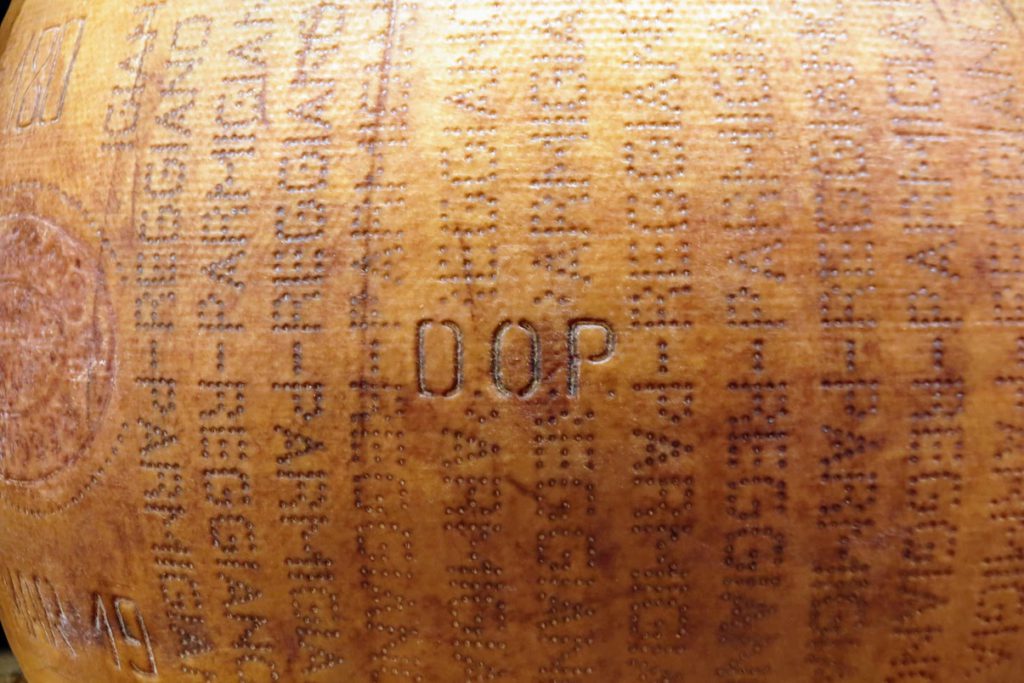

The next stage is to put each lump into the cheese moulds. These have a plastic lining embossed with all kinds of details of date, time and place, as well as a number that tells if the cheese was made in Reggio Emilia, Parma, Modena or Mantua

This information embeds itself permanently into the rind as it forms, meaning the cheese has a ‘signature’ that’s impossible to fake or remove. Apparently though they are also experimenting with putting a microchip in the cheese to make it even easier to check provenance. As I say, there is big money in forgery and this product is so fine that the consumer has to be protected.

The cheeses then head off for a relaxing salt bath for about three weeks. Here modern machinery is used to do the regular lifting and turning. These cheeses are very heavy at this point, being still full of moisture. In the old days it must have been very tough work.

Age is key

The cheeses once out of their briny bath are never aged for less than 12 months. At this stage the aroma is of fresh fruit, grass and flowers and the cheese is almost sliceable. After 24 months the crumbliness develops, while at 36 months spicier notes arrive. 36 months is usually the cut off point for general consumption, but some cheeses are pushed on to 48 which is a bit of a connoisseur’s cheese.

The cheeses are stored for all this time in vertiginous racks in massive temperature controlled rooms, and regularly tested by tapping them with a special hammer, as has been done down the ages.

The sound it makes is just a dull thud to my ears, but it tells the experts how well the cheeses are maturing and any subtle tone variation will also reveal any fissures hidden inside the cheese. A fissure means the cheese, while perfectly good in every other way, must be rejected for sale as a whole cheese, the identifying rind will be removed and it will be broken up and used to make high quality ground Parmigiano Reggiano instead.

Cheese to please

The different ages result in cheeses for all occasions. The more mature being ideal for eating on their own as an aperitif, the irregular lumps really spreading the flavours onto the palate. Try some with a dab of honey and perhaps some walnuts.

Of course they are all delicious grated or shaved fresh onto salad or over pasta, but never please over seafood. Pasta with lots of butter, black pepper and grated Parmigiano Reggiano is a simple and delicious dish when made with such a quality ingredient.

It is of course delicious in a risotto, that final addition lifting all the flavours up

To keep a large block, which is a great investment, ideally wrap it in greaseproof paper, vac pack it, and put it in the fridge (never the freezer). It should be brought out to room temperature at least an hour before eating so the aromas and flavours reawaken.

If you have a large pestle and mortar then grate Parmigiano Reggiano in, then add the best basil you can find, pine nuts, garlic and olive oil to make the very besto pesto.

So don’t just use Parmiggiano Reggiano for your spag bog! This versatile cheese has taken a long time to get to your kitchen, so take the time to make the very best of it.

#tasteofeurope #enjoyitsfromeurope #parmigianoreggiano #parmesan #euquality @parmigianoreggianouk

I ate my pesto on some focaccia, washing it down with clean, sharp,

I ate my pesto on some focaccia, washing it down with clean, sharp,